Workmen broke ground on Salisbury House almost a century ago. Beginning in 1923, truckloads of brick, mortar, barrels, and beams navigated the steep rise of the hill atop Tonawanda Drive. Over the next five years, the Weekses’ grand new home took shape. Local photographers captured in-progress images of Salisbury House at different stages of the project. These shots were primarily taken at a distance, and typically showcased the building’s stately dimensions. However, closer inspection of these photographs reveals the ordinary, work-a-day experiences of life at a 1920s construction site.

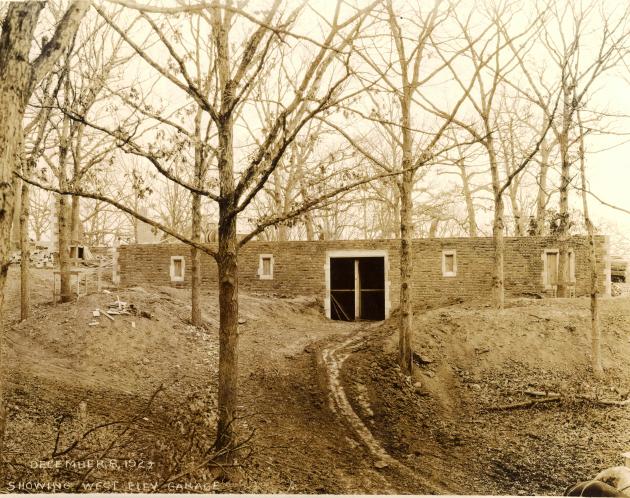

The photograph below from December 1923 shows a view of the garage taken from the west. At first glance, the photograph suggests little more than mud, building detritus, and desolation.

A closer look reveals action and purpose. Men stride across the half-finished garage. On the left, a man in a hat and overcoat, closely followed by an associate, looks north. Behind them, two more men continue their labors. The far left side of the photograph also includes details of men at work. Look closely at the corner of the structure in the foreground:

Two years later, thanks to the efforts of these men, a substantial amount of progress had been made. By March 1925, the main footprint of Salisbury House was apparent. The garage – featured prominently in the images above – is barely visible on the far left side of this photograph.

Though the exterior walls have taken shape, a closer look at this image shows a house far from complete.

The east wing of the house extends only to the first floor. Carl’s and Edith’s bedrooms remain but a twinkle in the architects’ eyes. There is no trace of the sixteenth-century, half-beam ceiling in the Great Hall. Daylight and oak trees crown the room instead.

A view of the north entrance tells a similar story.

The application of the famed flint-work on the Tudor wing of the house appears in progress on the left side of the frame.

The two men in this photograph illustrate the human realities of building Salisbury House. The man on the right was possibly an architect from Boyd & Moore, the local firm responsible for the design and build of the house (perhaps even Byron Bennett Boyd or Herbert J. Moore). As for the man on the left – perhaps a crew foreman? Their markedly different attire certainly suggests differences in occupation and/or class.

Progress marked the entire property in this spring of 1925. Below, the northeast approach to Salisbury House neared completion.

Our homburg (or fedora?) -wearing gentleman from above appeared again.

The three men in the foreground dwarf the workmen (at right in the full-sized photograph) who continued to toil away while the bosses posed for the camera.

Another wonderful detail appears in this photograph. The driveway slope dominates the image’s middle distance, with the majestic silhouette of Salisbury House beyond. Near the crest of the rise, a sign appeared at the base of a tree.

WILD FLOWERS IN IOWA ARE GETTING SCARCE ONLY THE UNINFORMED GATHER THEM

This sounds like Edith’s doing, as she was an enthusiastic gardener. To modern-day sensibilities, the sign suggests a vague similarity to the current mania for pet-shaming signs. If this sign were hanging around the neck of one of the Weekses’ canine companions – perhaps after a dig through the Salisbury gardens – they would have had an instant meme on their hands.

Four months after these photos were taken, the progress of construction was documented again. A view from the southeast corner of the property indicated that the workers had been busy during the summer of 1925.

Still, as yet there were no windows in much of the house, including the Common Room and Edith’s Suite.

At this point, the Weekses were two years into a five-year, three-million-dollar project. The pane-less windows, a cluster of barrels, and pile of dirt at photo’s right edge were visible reminders of the work still underway.

The view from the north in August 1925 also showed both the great distance already traveled by the Salisbury House builders, and the sizable amount of work left to finish. Here, the cottage appeared mostly finished – with windows, even! – and a tar-papered roof was in evidence.

Still, the main section of the house remained windowless.

Makeshift scaffolding and ladders also appeared. Although no workmen were featured in this particular photograph, evidence of their labor remained in the objects they left behind.

A comparison of photos separated by almost a century offers an amazing study in contrast.

Five years after the first truckloads of bricks and mortar rumbled up Tonawanda Drive, Salisbury House was complete. The total cost of building and furnishing the home – three million dollars in the 1920s – would be about forty million dollars today.

A local pastor read a blessing during the laying of the house’s cornerstone in 1925. Nelson Owen, the rector of St. Paul’s Church, urged the Almighty to “bring this home to a happy completion.” For Salisbury House – still standing, still magnificent – the preacher’s benediction rang true.

2 replies on “Bricks, Mortar, & Men”

[…] images of the new home’s interior. These photographs, particularly when paired with exterior construction images, make a fascinating early study of the […]

[…] the painting, though he declined to buy it at the time due to his current financial situation with building the massive Salisbury House […]